Custom Solutions at

AI Speed

Aboard is the world’s first solution engineering firm. Our team of experts uses our AI-powered platform to deliver your business software in record time.

The Landscape

Aboard = Platform + People

Your off-the-shelf software isn’t living up to your business’s ambitions. Or you’re tired of relying on one-size-fits-none SaaS tools. It’s all held together with spreadsheets, clutch team members, and chewing gum.

You’re losing money through all this friction. We have a better way, and people are the solution: our people and your people.

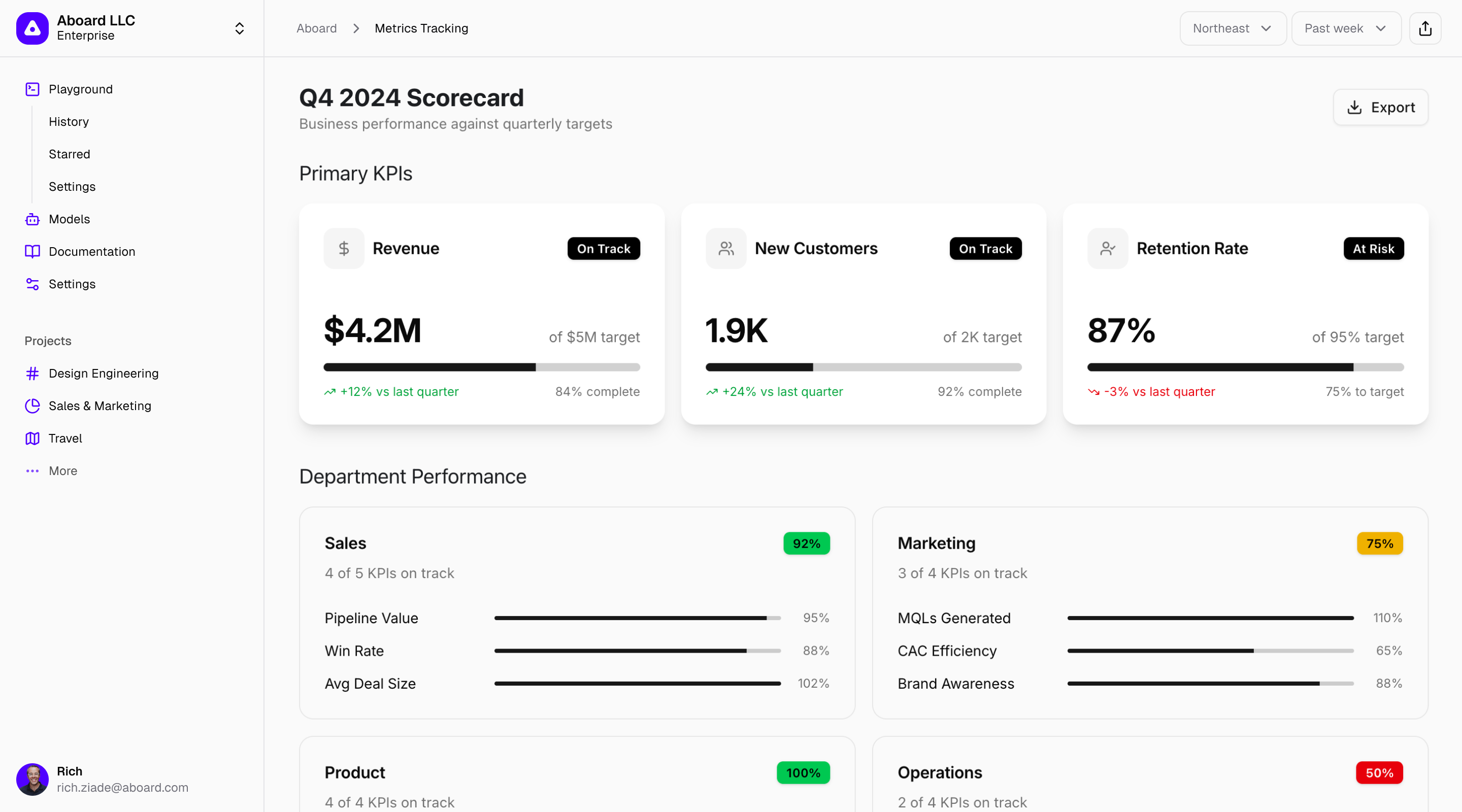

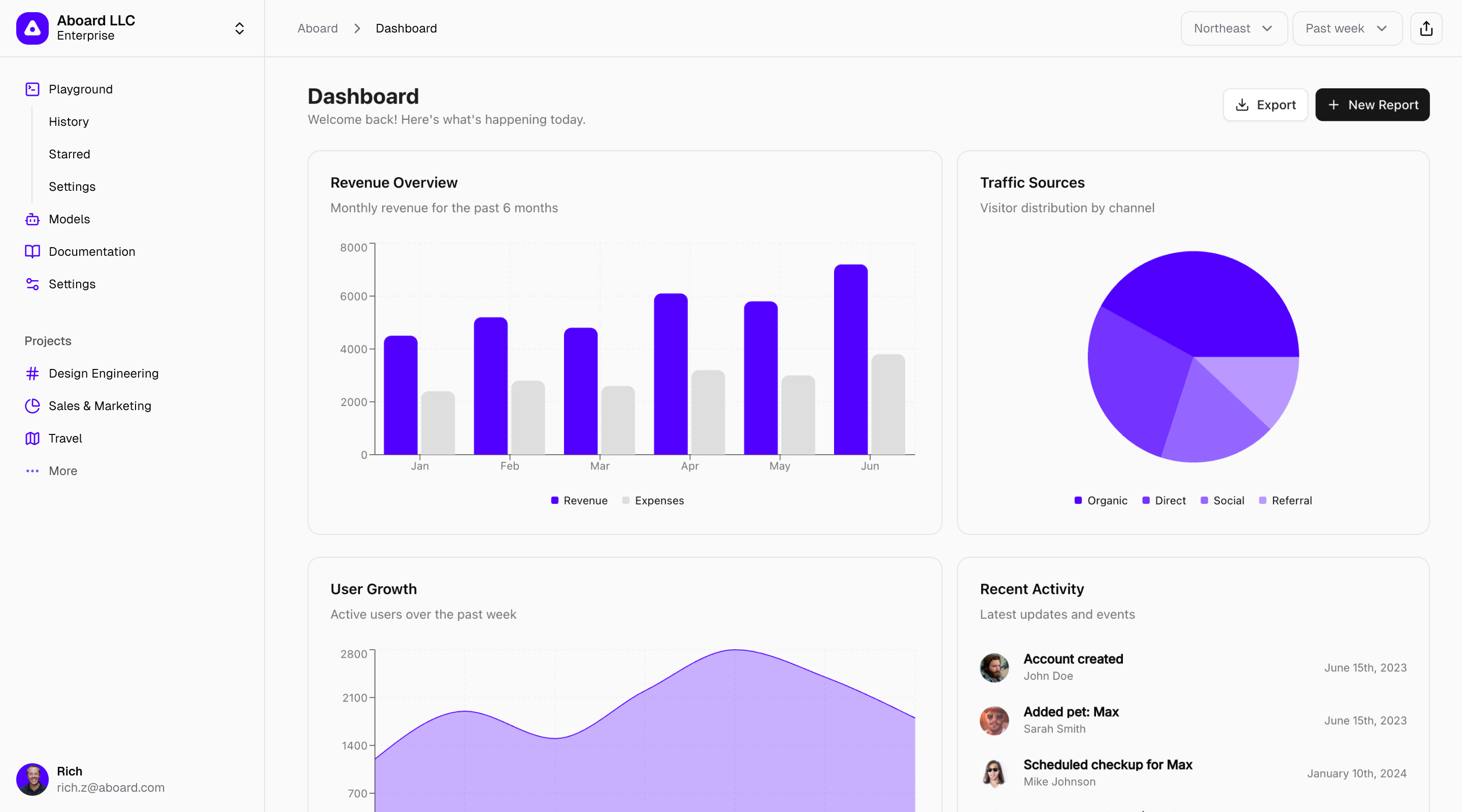

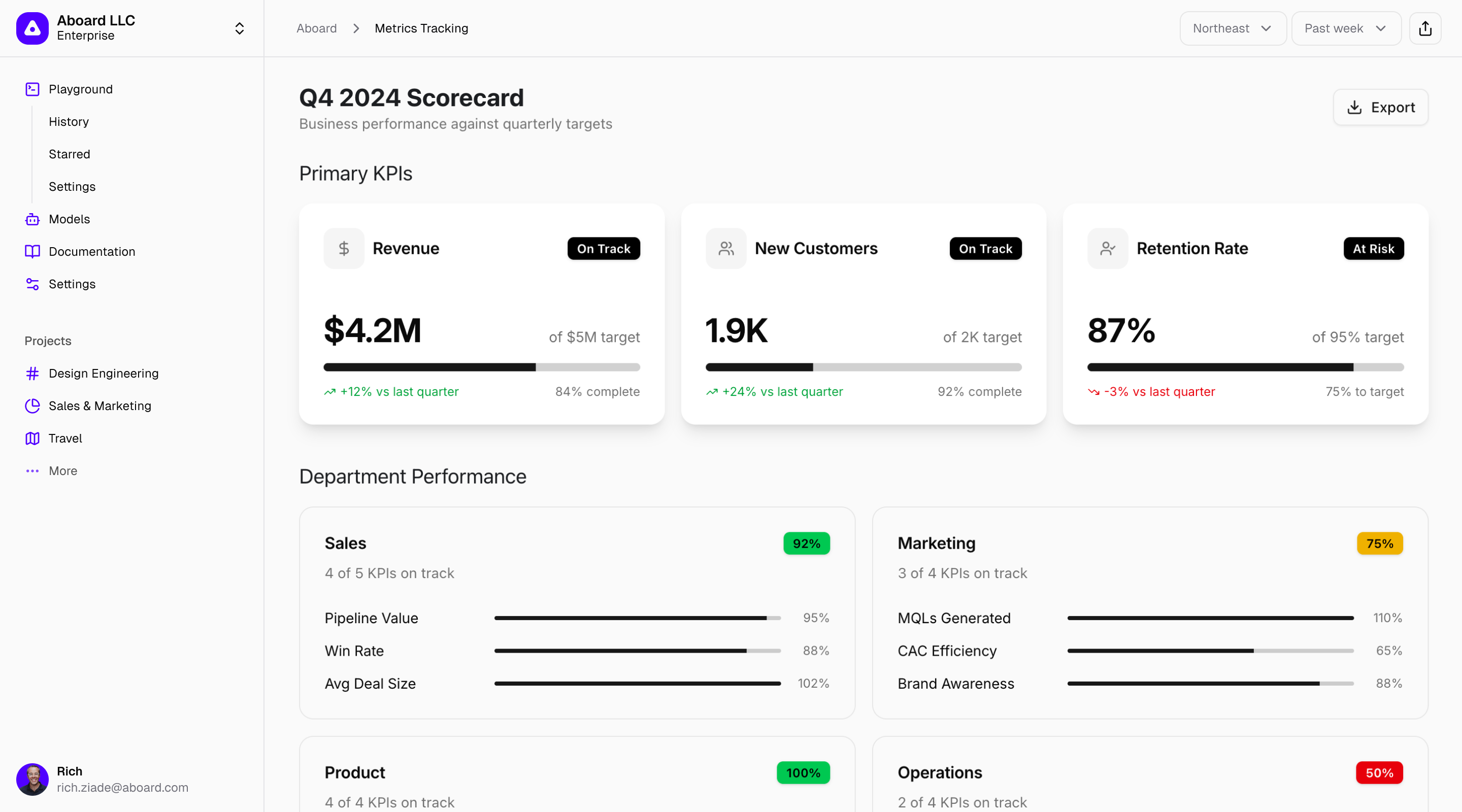

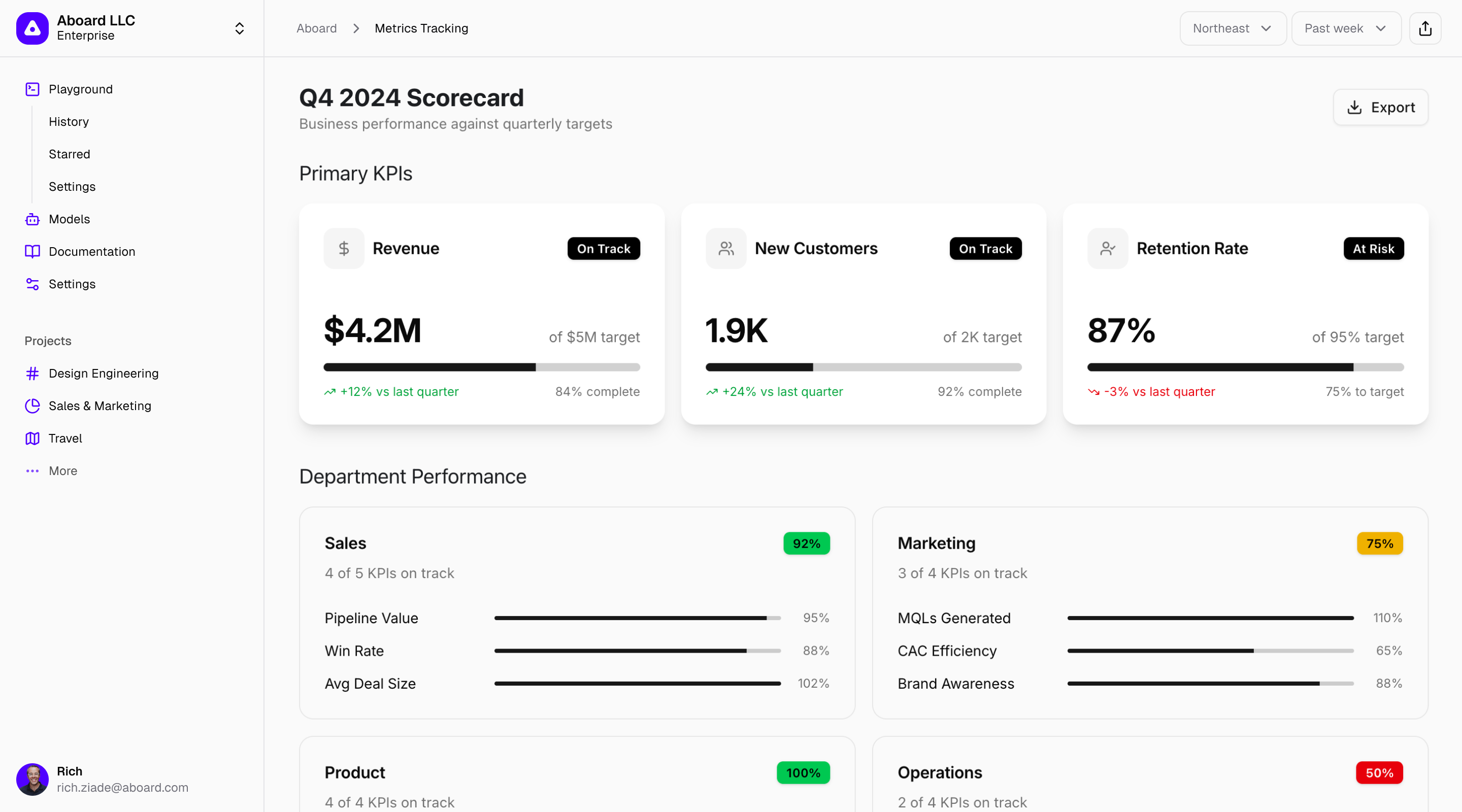

Metrics trackers custom tailored to your business

World-class Solution Engineers

If your software isn’t growing with you, you need a partner who listens. Our speciality is in finding unifying solutions. We use AI to deliver world-class software at a reasonable monthly cost. We can ship quickly, bring your data in today, and make your business stack better.

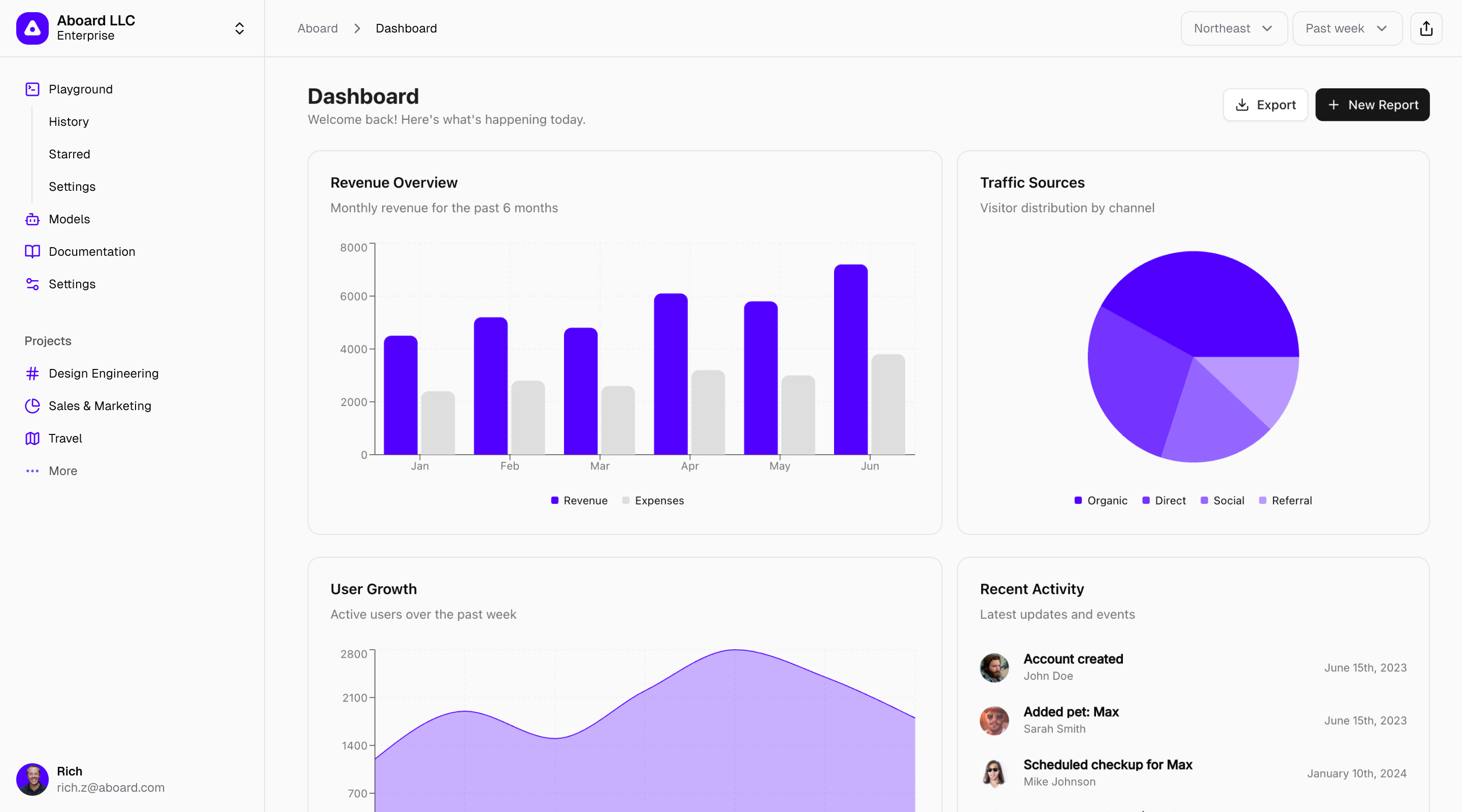

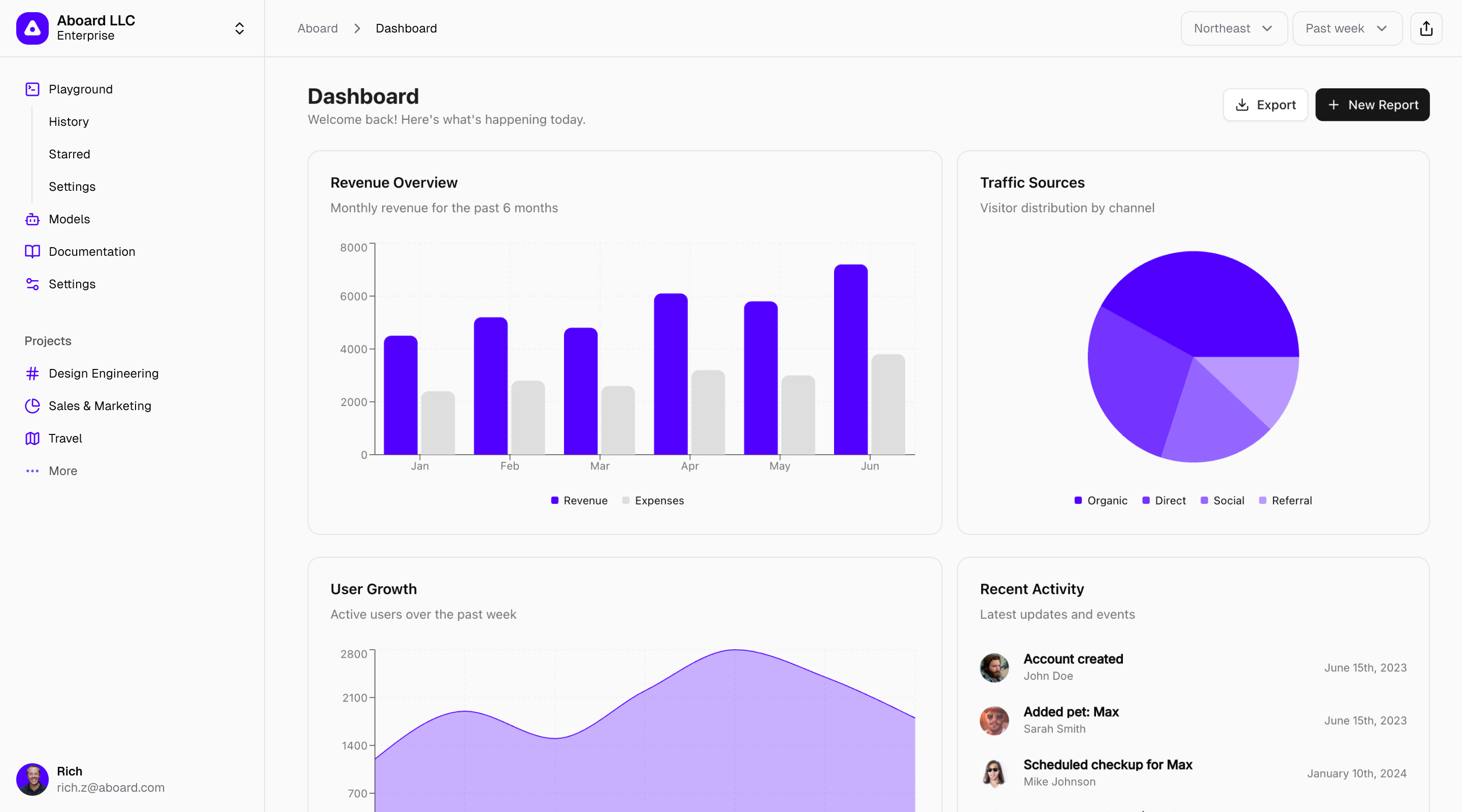

Stop adapting to their dashboards. Define your own

AI-driven Software that Truly Ships

95% of AI software initiatives fail. That’s because the last mile is truly long. We solved that. Aboard’s custom platform, when operated by a skilled solution engineer, can deliver fully functioning, reliable, stable digital business software in a fraction of the time of other tools—as unique as your business and your team. Here's a peek at what our software development platform can prototype in minutes.

What We Do

Let us show you how it works.

Here’s how we work with you to identify problems, develop an approach that combines software, data handling, integrations, and more, iterate software, and ship your solution, all in record time.

We’re something new, and we take you from idea to deploy, at the highest level of quality, in record time.

Platform

CRM, ERP, CMS, project management, and dashboards galore. We can do it all—fast.

We use AI to radically accelerate the software development lifecycle. Our Solution Engineers partner with you, learning your pain points, critical needs, and how your data and integrations need to evolve. They can design, prototype, and explore applications—often in minutes—using Aboard’s proprietary AI-accelerated platform. Then they keep iterating with your feedback until the software takes shape: familiar, secure, powerful, and integrated with any legacy systems.

01

Blueprint

+

02

Aura

+

03

Lens

+

04

Workbench

+

Case Studies

We deliver solutions and transform businesses

Make an Impact: Partner Health Analytics Platform

Transforming Health Data into Strategic Insights with AI-Accelerated Development

SageSure Policy Logic Central

Automating Insurance Policy Validation with AI-Accelerated Development

About

About Aboard

Our mission is to ship custom software for organizations by leveraging AI-powered tools to give companies right-sized, low-friction software to run their business better.

Over the years, our team has provided solutions to thousands of users across Fortune 100 companies and giant NGOs. We’re not just another AI tool; we’re your partner in shipping the robust business software that drives real growth.

Built with lessons from these partners

Rich Ziade

/

CEO

A serial software entrepreneur and agency veteran, Rich Ziade has worked with the world’s biggest companies and built and sold many companies of his own, including Readability, Arc90, and with Paul, Postlight. Rich started his career as a lawyer, but rapidly became enchanted with technology and business automation, and is still at it.

Paul Ford

/

President

One of the world’s leading technology thinkers, Paul Ford has written about the way that software works for dozens of publications like Wired, Businessweek, and the New York Times. After years of writing about technology, Paul decided to do something about it—and he keeps doing so, year after year.

More Aboard

The Aboard Podcast

Software in the Age of AIJoin Rich Ziade, Paul Ford, and their guests as they discuss how AI is changing software development, business strategy—and everything else.

Latest episodes

From Paul Ford and Rich Ziade: Weekly insights, emerging trends, and tips on how to navigate the world of AI, software, and your career. Every week, totally free, right in your inbox.

Latest newsletters

Get in Touch

We Can Help

Please fill in the form to get in touch

© Aboard 2026. All rights reserved

Custom Solutions at

AI Speed

Aboard is the world’s first solution engineering firm. Our team of experts uses our AI-powered platform to deliver your business software in record time.

The Landscape

Aboard = Platform + People

Your off-the-shelf software isn’t living up to your business’s ambitions. Or you’re tired of relying on one-size-fits-none SaaS tools. It’s all held together with spreadsheets, clutch team members, and chewing gum.

You’re losing money through all this friction. We have a better way, and people are the solution: our people and your people.

Metrics trackers custom tailored to your business

World-class Solution Engineers

If your software isn’t growing with you, you need a partner who listens. Our speciality is in finding unifying solutions. We use AI to deliver world-class software at a reasonable monthly cost. We can ship quickly, bring your data in today, and make your business stack better.

Stop adapting to their dashboards. Define your own

AI-driven Software that Truly Ships

95% of AI software initiatives fail. That’s because the last mile is truly long. We solved that. Aboard’s custom platform, when operated by a skilled solution engineer, can deliver fully functioning, reliable, stable digital business software in a fraction of the time of other tools—as unique as your business and your team. Here's a peek at what our software development platform can prototype in minutes.

What We Do

Let us show you how it works.

Here’s how we work with you to identify problems, develop an approach that combines software, data handling, integrations, and more, iterate software, and ship your solution, all in record time.

We’re something new, and we take you from idea to deploy, at the highest level of quality, in record time.

Platform

Our platform utilizes a set of tools we created to help you harness the power and speed of AI.

We use AI to radically accelerate the software development lifecycle. Our Solution Engineers partner with you, learning your pain points, critical needs, and how your data and integrations need to evolve. They can design, prototype, and explore applications—often in minutes—using Aboard’s proprietary AI-accelerated platform. Then they keep iterating with your feedback until the software takes shape: familiar, secure, powerful, and integrated with any legacy systems.

01

Blueprint

+

02

Aura

+

03

Lens

+

04

Workbench

+

Case Studies

We deliver solutions and transform businesses

Make an Impact: Partner Health Analytics Platform

Transforming Health Data into Strategic Insights with AI-Accelerated Development

SageSure Policy Logic Central

Automating Insurance Policy Validation with AI-Accelerated Development

About

About Aboard

Our mission is to ship custom software for organizations by leveraging AI-powered tools to give companies right-sized, low-friction software to run their business better.

Over the years, our team has provided solutions to thousands of users across Fortune 100 companies and giant NGOs. We’re not just another AI tool; we’re your partner in shipping the robust business software that drives real growth.

Built with lessons from these partners

Rich Ziade

/

CEO

A serial software entrepreneur and agency veteran, Rich Ziade has worked with the world’s biggest companies and built and sold many companies of his own, including Readability, Arc90, and with Paul, Postlight. Rich started his career as a lawyer, but rapidly became enchanted with technology and business automation, and is still at it.

Paul Ford

/

President

One of the world’s leading technology thinkers, Paul Ford has written about the way that software works for dozens of publications like Wired, Businessweek, and the New York Times. After years of writing about technology, Paul decided to do something about it—and he keeps doing so, year after year.

More Aboard

The Aboard Podcast

Software in the Age of AIJoin Rich Ziade, Paul Ford, and their guests as they discuss how AI is changing software development, business strategy—and everything else.

Latest episodes

From Paul Ford and Rich Ziade: Weekly insights, emerging trends, and tips on how to navigate the world of AI, software, and your career. Every week, totally free, right in your inbox.

Latest newsletters

Get in Touch

We Can Help

Please fill in the form to get in touch

© Aboard 2026. All rights reserved

Custom Solutions at

AI Speed

Aboard is the world’s first solution engineering firm. Our team of experts uses our AI-powered platform to deliver your business software in record time.

The Landscape

Aboard = Platform + People

Your off-the-shelf software isn’t living up to your business’s ambitions. Or you’re tired of relying on one-size-fits-none SaaS tools. It’s all held together with spreadsheets, clutch team members, and chewing gum.

You’re losing money through all this friction. We have a better way, and people are the solution: our people and your people.

Metrics trackers custom tailored to your business

World-class Solution Engineers

If your software isn’t growing with you, you need a partner who listens. Our speciality is in finding unifying solutions. We use AI to deliver world-class software at a reasonable monthly cost. We can ship quickly, bring your data in today, and make your business stack better.

Stop adapting to their dashboards. Define your own

AI-driven Software that Truly Ships

95% of AI software initiatives fail. That’s because the last mile is truly long. We solved that. Aboard’s custom platform, when operated by a skilled solution engineer, can deliver fully functioning, reliable, stable digital business software in a fraction of the time of other tools—as unique as your business and your team. Here's a peek at what our software development platform can prototype in minutes.

What We Do

Let us show you how it works.

Here’s how we work with you to identify problems, develop an approach that combines software, data handling, integrations, and more, iterate software, and ship your solution, all in record time.

We’re something new, and we take you from idea to deploy, at the highest level of quality, in record time.

Platform

Meet the Aboard Platform

We use AI to radically accelerate the software development lifecycle. Our Solution Engineers partner with you, learning your pain points, critical needs, and how your data and integrations need to evolve. They can design, prototype, and explore applications—often in minutes—using Aboard’s proprietary AI-accelerated platform. Then they keep iterating with your feedback until the software takes shape: familiar, secure, powerful, and integrated with any legacy systems.

01

Blueprint

+

02

Aura

+

03

Lens

+

04

Workbench

+

Case Studies

We deliver solutions and transform businesses

Make an Impact: Partner Health Analytics Platform

Transforming Health Data into Strategic Insights with AI-Accelerated Development

SageSure Policy Logic Central

Automating Insurance Policy Validation with AI-Accelerated Development

About

About Aboard

Our mission is to deliver high-quality custom software faster and cheaper by using Aboard’s AI-powered platform, operated by skilled solution engineers.

Over the years, our team has provided solutions to thousands of users across Fortune 100 companies and giant NGOs. We’re not just another AI tool; we’re your partner in shipping the robust business software that drives real growth.

Built with lessons from these partners

Rich Ziade

/

CEO

A serial software entrepreneur and agency veteran, Rich Ziade has worked with the world’s biggest companies and built many companies of his own, including Readability, Arc90, and, with Paul, Postlight. Starting his career as a lawyer, Rich took his experience of large-scale business automation to become a pioneer in building API-powered business systems at scale.

Paul Ford

/

President

One of the world’s leading technology thinkers, Paul Ford has written about the way that software works for dozens of publications like Wired, Businessweek, and the New York Times. After years of writing about technology, Paul decided to do something about it—and he keeps doing so, year after year.

More Aboard

The Aboard Podcast

Software in the Age of AIJoin Rich Ziade, Paul Ford, and their guests as they discuss how AI is changing software development, business strategy—and everything else.

Latest episodes

From Paul Ford and Rich Ziade: Weekly insights, emerging trends, and tips on how to navigate the world of AI, software, and your career. Every week, totally free, right in your inbox.

Latest newsletters

Get in Touch

We Can Help

Please fill in the form to get in touch

© Aboard 2026. All rights reserved