Beeps of Yore

Learning from messy tech pasts via the history of the synthesizer industry.

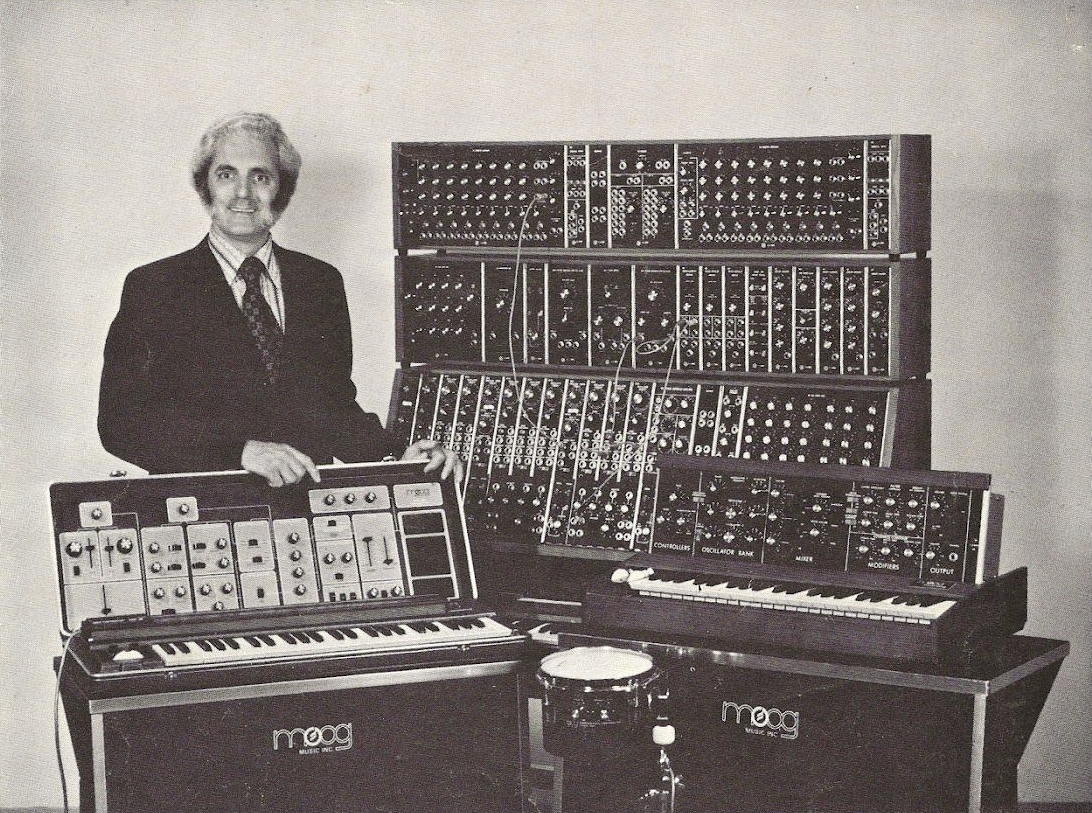

Bob Moog and friends. For a certain kind of person this image produces a profound “standing outside the window wearing a shirt that says SICKOS, saying ‘YES…HA HA HA…YES!’” kind of emotion. From Wikipedia.

I recently read a book called Analog Days by Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco, about the early history of synthesizers. It’s a good book, and filled in a lot of gaps in my knowledge. I read it because I know a lot about the history of computing, but less about how other technologies showed up in our market-driven world, and because I am a huge synth nerd as a hobby.

Much of the book is focused on Bob Moog (rhymes with “rogue”) and his eponymous synths, which were born into the high flower of hippiedom in the 1960s. Moog was a bad businessman—basically a gentle soul who really liked transistors, and was deeply bemused by the bananacakes stoners who kept doing weird stuff with his gear.

What surprised me—and why I’m sharing this—is how ridiculously familiar it all seemed. Selling synths in the 1960s doesn’t seem that different from selling software sixty years later. Three things stuck out:

Want more of this?

The Aboard Newsletter from Paul Ford and Rich Ziade: Weekly insights, emerging trends, and tips on how to navigate the world of AI, software, and your career. Every week, totally free, right in your inbox.

First, everyone thought they were doing something else. Reinventing music, creating art, smashing the capitalist system by producing musical freakouts, whatever. Moog originally made theremins (which are electrical antennae that you wave at and they go “whooooo…wheeeeee…whooooo”) and only backed into putting a keyboard on a synth much later. His most successful product, the Minimoog, was a skunkworks project glued together from factory trash while he was off failing to sell bigger things. It saved the company, for a while, by accident.

This is the story of every technology: We thought the web was for journal articles, but it’s mostly for video and commerce. We thought people would all line up to use virtual reality, or bitcoin, or wearable technology—and some do, but mostly, they chat on their phones. Someone creates a microblogging platform to share little life updates and a big chunk of society organizes around it. We’re guilty of it at Aboard—we insist we’re operating from grand strategy, but I have to admit, most of our strategy is just reacting quickly while making eye contact.

As always happens, in the synth world, utopian visions competed with market realities. Putting a keyboard on a synth and playing “traditional” music seemed like selling out. Synth music like “Switched on Bach” seemed like musical revanchism. There’s always a cohort that says, “You are not embodying the true spirit of the technology!” Or that the new thing will ruin everything. Right now people are very angry about a lot of tech things, and next year they will be angry about new ones. Sometimes they’re right.

Second, sales and marketing ultimately determined everything. Moog did events with…Taco Bell. Both were new, so put them together! (Experiential marketing and cobrands.) Moog’s main salesman would loan synths out to musicians, they’d get hooked on them, then he’d “break” the synth while they were at a show by removing a component. After the show he’d come back and “fix” it, and then they’d yell at him—and he’d counter that if it was that important to them, they should get their girlfriend to loan them money enough to buy it. Brutal, effective. (Freemium model.) And then came the endorsements—Stevie Wonder showed up in ads for a Moog competitor, ARP. (Influencer marketing.) ARP kept hammering Moog for going out of tune. Everyone started to sue everyone else and use patents defensively. Eventually Yamaha made cheaper all-digital synths in Japan and sold more than anyone. Pricing always shows up in the end. It’s the ultimate sales tool.

Third, we get obsessed with our new toys and pay a social price. Bob Moog has taken the bus down from his little factory in Trumansburg, New York, to Manhattan, and is about to install the very first synthesizer for a guy who does TV jingles, Eric Siday. It’s a big hulking bunch of boxes and wires, barely an instrument. He tells it this way (slightly censored to keep your corporate profanity filters from bouncing the email):

It’s eight o’clock in the morning and Edith [Eric’s wife] is watching … from one of the doorways. I put one of the boxes down and take the lid off and take all the packing out and spread it on the hall floor. Take one of the instruments out and set it up. Begin to unpack the next box and I didn’t realize this, but Edith is slowly losing control of herself. She’s watching this. I was busy unpacking. I’m setting the second box up … All of a sudden she loses control of herself completely. She screams out, “Eric, more s*** in this house. All you ever do is bring s*** in this house. One piece of s*** after the other!” … and somehow I got the instrument set up and [got] out of there that day.

The main lesson of the book for me is that technology should be exciting, but business should be boring. The story of early synthworld is the story of people who are really, really into what they are doing, and are always in a situation where they have to innovate their way out of a hole. Occasionally that can work, but every few chapters, someone would bet a company on a new product, put everything into it, and go out of business.

The problem is that “build an exciting product inside of a boring business” sounds great, but it’s hard, because exciting products come out of risk and fear, not out of better accounting principles. You can’t optimize your way to innovation. So I’ve been thinking and talking with my co-founder Rich—who also loves tech probably a little too much—quite a bit about what makes a business “just boring enough” that it can keep being weird but start making money. We want to be here for the long haul.